I’ll try to have my review by the end of the weekend. Watch below:

Ryan Griggs Comments on Episode 1

Friend of Crash Course Criticism and Austrian scholar, Ryan Griggs, has written his own critique of the first episode of Crash Course.

Something I had not considered, Ryan observed Mr. Clifford’s choice of words in calling scarcity and cost “assumptions”:

Let’s start at beginning. Jacob identifies two “assumptions” in economics, the first of which is “scarcity.”

Scarcity is not an assumption. Scarcity is a reality.

Men (and women) have unlimited ends and limited means with which to achieve those ends. These means are necessarily scarce. This is a fact of life, not an assumption.

Jacob’s second assumption is that “everything has a cost.” Well clearly, if means (including time) are scarce, then men must ordinally rank (1st, 2nd, 3rd…) the ends they would like to achieve in the order that they would like to achieve them. In other words, the individual must choose one end over another, over another, and so forth. The first end foregone (2nd ranked end) is the cost of obtaining the first-ranked end. Therefore, scarcity implies cost, because man must choose one end–instead of another–to achieve first. Therefore, cost is a fact of life too, not an assumption.

Ryan also details a subject I have only touched on, but not delved into: the classification of economics as a social vs. physical science. He writes:

A famous economist writes, “it is a mistake to set up physics as a model and pattern for economic research” (Human Action, p. 6). The scientific method (verificationism) is appropriate for the physical sciences, because it’s subjects aren’t human. This sounds silly, but it’s implications are vast. Chemicals, electricity, rocks, and other elements of nature do not act. Humans are unique in that they are capable of cognition, identifying ends and ranking them according to their preferences. This fundamental distinction means that the method of study in the physical sciences is not appropriate for the social science of economics. After all, its subjects–humans–are inherently different than the subjects of the physical sciences.

Please read Ryan’s full post at his blog.

Why Didn’t Economists Predict the 2008 Financial Crisis?

This was a great question Mr. Clifford brought up in the first video, but then never answered:

People sometimes criticize economists asking “Why didn’t they predict the 2008 financial crisis?” or “Why can’t they agree on what the government should do or shouldn’t do when there’s a recession?”

These criticisms fails to distinguish between Macroeconomics and Microeconomics. Specifically, all these complaints are about Macroeconomics.

He then goes on to define and explain the differences between Macro and Micro, without ever coming back to the original questions. Let’s go back to them. First, the easy one:

Why can’t economists agree on what the government should do or shouldn’t do when there’s a recession?

As mentioned in previous posts, economics has many different theories and different schools of thought. Economists can’t agree on how to respond to a recession because they don’t all believe the same principles of economics. For example, some think government spending helps an economy get out of a recession, while others think that government spending hurts the economy. So it’s not a surprise that these different beliefs in the fundamentals of macroeconomics lead to different suggestions on what the government should do.

Asking this question is similar to “Why can’t politicians agree about what to do about [policy topic]?”

Why didn’t economists predict the 2008 financial crisis?

This is a great question. If you were watching CNBC or Bloomberg in 2007, you would not hear any debate as to whether we were headed for a recession. After all, the stock market was up, unemployment was down, and you just bought a house with no money down! The economy was looking good.

There were, however, people who warned against the impending financial collapse, primarily from the Austrian school. They even made some television appearances, where they were ridiculed and laughed at on just about every program:

Does this necessarily mean that the Austrian school was right because they were the ones who predicted the crisis? It doesn’t, but it would be disingenuous to say that “economists did not predict the 2008 financial crisis.” Some of them did.

The argument against this, of course, is “a broken clock is right twice a day.” In other words, if you always say that a crisis is coming, then you’re going to be right when it happens. In fact, right now many Austrians are warning of an impending financial collapse, and some of them have even predicted dates of the crisis which have now passed. We’ll get to this more when we talk about economics as a social science vs. physical science, but Austrians are often characterized as “doom and gloomers” who always warn that we are close to the next crisis.

However, if you watch the video above, Peter Schiff isn’t only predicting a recession, he says exactly how it’s going to happen:

Today’s home prices are completely unsustainable. They were big up to these artificial heights by a combination of temporarily low adjustment-rate mortgage payments by a complete absence of any lending standards and by speculative buying.

That’s awfully specific, and even if he was wrong about the year (he clearly jumped the gun by saying the crisis would happen in 2007), the fundamentals are pretty dead on from what we know about the recession today.

So take this for what it’s worth: Austrians are not great at predicting the timing of recessions (but then again, neither is anyone), but the explanation behind it seems pretty solid.

Keynesian Presuppositions

John Maynard Keynes is probably the most influential economist in currently-practiced economic policy. Among the Keynesian marks left on economics is the idea of the necessity of government intervention to moderate the booms and busts of the economy. As the theory goes, governments must spend during a recession to stimulate the economy.

This idea makes a lot of sense if you’re hearing it for the first time. When you’re tired, coffee helps you get back to normal, and similarly, if the economy is down, you need to kickstart it with some spending to get the ball rolling again.

Adriene alludes to this idea when she says:

Economics is the government deciding whether to increase its spending when there’s a recession, and if it’s worth going into debt.

Usually the answer is yes, increase spending, as the United States did with its $831 billion Stimulus Package (also known as the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009).

The problem with testing economic theories is that you never know if it actually works. The 2009 Stimulus Package did not have the kickstarting effect that was predicted; the free-market economists said that this was because Keynes’s theory is wrong and government spending does not help the economy because a stimulus package would only take money from the more efficient private sector economy (through taxation) and transfer it to a less productive public sector economy. However, Keynes supporters argue that Keynes is correct and the Stimulus Package did work, and the situation would have been much worse if the government had not intervened.

Unfortunately, we’ll never know the truth empirically, since economics is not a physical science where you can have an identical “control group” economy to compare it to. And while Adriene’s point didn’t directly claim Keynes’s theory to be true, she did imply it. By presenting the downside of spending as “going into debt,” which isn’t necessarily true, she doesn’t mention what real dissenters of stimulus spending would argue: that stimulus packages are a net negative for the economy, even if the country doesn’t have to borrow money to pay for it.

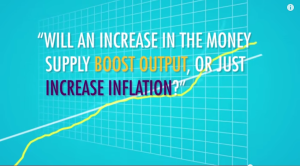

Mr. Clifford makes another Keynesian presupposition when he posits this question as an example of macroeconomics:

Will an increase in the money supply boost output, or just increase inflation?

Framing the question this way essentially presupposes that increasing the money supply can boost output, but the risk is that it may also increase inflation.

This is also derived from Keynes’s theory of government intervention for a recessed economy: increasing the money supply (i.e. creating money and buying financial products with them) will give more money to banks who then lend out that money to people for long-term capital projects (building construction, investing in companies, etc.). Now there’s more money circulating in the economy as more people get to borrow money to fund their projects, and the financial industry is booming because they are the first ones to get the newly-printed money. However, printing money runs the risk of prices increasing as the dollar becomes less valuable. The Keynesian theory describes money creation as a balancing act; the government needs to print just enough to kickstart the economy, but not too much to create an inflation problem.

Again, real dissenters from Keynesian economic theory (or at least those who follow the Austrian Business Cycle) would argue that increased inflation is not the only risk of increasing the money supply. As the Austrian theory goes, money printing distorts the economy, shifting production from consumer goods (like stuff you buy at CVS) to capital goods (projects that banks give big loans to). The shift is harmless at first and may even appear to boost the economy, however, this distortion that provokes an artificial boom will ultimately result in an even greater bust. In other words, the cups of coffee you drank to wake you up will leave you with a bigger caffeine withdrawal the next day.

With these two examples, it’s not too hard to see a preference toward Keynesian macroeconomics, but who can blame them? Keynesianism is widely-practiced in countries around the world and is supported by many economists.

The least they can do, however, is correctly present the real concerns about Keynesian policies, and not the Keynesian concerns about Keynesian policies.

Meet Our Co-Hosts

You may be interested in who is teaching us economics in this Crash Course series and what their backgrounds are. Keep in mind this is the first Crash Course series not hosted by either of the founders, John and Hank Green.

Jacob Clifford teaches high-school economics at San Pasqual High School in Escondido California. He is the founder of ACDC Leadership, a website for “student-focused teaching resources that makes learning exciting, powerful, and fun.” Mr. Clifford has released his own YouTube videos that explain economics for his students. It’s obvious why Crash Course chose this guy to be a co-host: he pretty much does the same thing as Crash Course but with a smaller budget. He also has a pretty high ratemyprofessor score.

Mr. Clifford received his Master’s in Economics from the University of Delaware.

If you recall, his part of the show is going to talk about “theories and graphs of economics, you know, the textbook stuff,” so it makes sense that he knows the high school economics textbook front-to-back.

Adriene Hill is a Senior Reporter of the public radio show Marketplace, where she’s been there for five years. Most of her news segments are about Media & Technology, but she also seems to follow the Greece Debt Crisis pretty closely. Her role is to talk about real world applications and examples of economics to relate Mr. Clifford’s theoretical points to stuff you’re familiar with. She has a Master’s in Political Science from Northwestern.

I’m not sure how they found Adriene Hill. Crash Course did have an agreement with PBS, but Adriene’s Marketplace is owned by American Public Media, a separate entity.

Any findings, thoughts, or conspiracy theories about how Crash Course found Adriene Hill, please let me know.

As far as I know, neither of the hosts have background in Austrian Economics or taken Tom Wood’s Liberty Classroom.

What is this course all about?

I heard a great quote recently that I should have paid better attention to:

“Of all your greatest heroes, none of them would read the comment section.”

But I did anyway, just to see what Crash Course fans would say about the introduction to the upcoming series. In fact, one of the top comments reflected my sentiment in my first post:

This seems like a reasonable request. Richie is asking for polycentric approach to economics instead of defaulting to neo-liberal economics. Someone took umbrage to his comment and wrote below:

To this person, the purpose of this course is to teach “high school AP economics.” In fact, this person seems frustrated that anyone would teach anything other than this.

First, nowhere on the intro video was there mention of this course’s educational intent. As far as we know, the mission statement is “to teach economics.” The series’ creator has complete creative control over the series, and I’m not familiar with any duty that Crash Course has to prepare students for their AP exams.

But poopisnotpoop’s comment begs the question. In other words, since economics is a polarizing topic for some and “truth” is not as clear as in mathematics or physics, how do you approach telling people how economics works? Do you talk about where economic ideas come from, how popular they are, and how they’ve been tested?

Most economists are familiar with the different schools of thought, but I doubt that any of them were introduced to the subject by understanding that there is not one accepted or “true” school. Different schools have different arguments and explanations for their theories, and certain schools and theories are more popular than others.

This is not how high school economics is taught, which is why most people have faith that there is one understanding of how things work, and that the government, who has the greatest control over the levers of the economy, is making the best decisions, given what we know about the “truths” of economics.

Crash Course Economics – Episode #1 in Review

Episode 1 of Crash Course gave a brief introduction to how the course is designed, who your co-hosts are, and some basic principles and definitions in economics. There was a mix of good and bad economic conclusions, so let’s dive right in:

How Does Crash Course Define Economics?

Our first co-host, Mr. Clifford, defines economics as “the study of people and choices”. This is a pretty great definition, especially considering the alternatives. Depending on his preferred school of economic thought, he could have easily said economics is the study of “classes and prosperity,” “institutions and planning,” or “statistics and predictions”. Instead, Mr. Clifford went with people and choices which will become important later on when the show gives examples of choices.

The Good

The first example of what a human choice looks like couldn’t be more relatable to the audience: watching a YouTube video. YouTubers compete for your attention, and by proxy, ad revenue. YouTube content is a serious business as our hosts know, and the popularity of some channels over others will determine the actual wealth of the content creators.

Our second co-host, Adriene, even goes into defining opportunity cost: “the cost of watching this video is the video you’re not watching.”

I would have been satisfied with this explanation, but Adriene goes so far as to give a great example of opportunity cost in having a large military state:

Military spending in the United States is over $600 billion per year. That’s close to what the next top 10 countries spend combined…the opportunity cost of [each] aircraft carrier could be hospitals, schools, and roads.

This statement is pretty profound in one sense, considering that some people and economists continue to write that any kind of government spending is good for the economy regardless of what it is, even if it’s for a fake alien invasion.

What is not mentioned, however, is that the opportunity cost of these aircraft carriers could also be non-government spending in the marketplace. In other words, if the money spent on aircraft carriers were refunded to taxpayers (or never taken in the first place), people could decide for themselves what they would prefer to spend that money on. It could be towards their healthcare bills, their kids’ college tuition, or buying consumer goods, any of which might be more important to them than another aircraft carrier.

This is a good example of Bastiat’s broken window argument or “the unseen”, which says that it’s easier to see the stuff paid for (in this case, the aircraft carrier) than that which could have paid for.

The Bad

The YouTube video selection example was a great illustration of the marketplace, but I thought next examples were a little strange.

“But what if I’m watching this at school,” you ask. “What if I’m forced to watch this?” Well, you weren’t forced to go to school. You could ditch, you could drop out, you could move to a country that doesn’t have compulsory education.

Wait, isn’t that a contradiction? Doesn’t something legally compulsory require coercion or force? Parents have a legal obligation to send their kids to school, under the threat of significant fines or jail time, sometimes for the student. It doesn’t matter if school gives you anxiety or you’re being bullied, you still have to go. And you obviously can’t just move to another country; runaways are sent back to their legal guardians.

This is quite different from choosing which YouTube video to watch. You don’t get fined or jailed for not watching a YouTube video. To a child, compulsory education is not the marketplace.

Another problem I had with the videos was a lack of distinction of individual and government action:

Is there a way to ensure there will never be another traffic fatality? Yes, we can crush all the cars, close the roads, and force everyone to walk. Do you want to decrease the number of people convicted of murder? You could decriminalize murder. You want to end the unethical treatment of elephants? You can kill off the elephants, in an ethical way of course.

Are these questions directed at me? I can’t do any of these things.

I can choose one YouTube video over another, but I cannot choose an alternative road system, legal system, or what other people do with their elephants.

You know driving has risks, that you might get in a car accident, but you still drive.

Adriene has now switched the subject to what I personally decide to take as my transportation method. The power to choose whether to drive is different from deciding to crush all the cars and force everyone else to walk. I have control over myself and my actions, but I don’t get to decide how other people act.

Assessment

I was pleased and entertained by the introductory episode of Crash Course Economics. The big economic principles it taught are generally unobjectionable, but some of the word selection and examples are either confusing or misleading. The 10-minute video has a lot more to unpack, and I’ll try to expound on some of the interesting choices of words and implications before the next video comes out. I’ll also include some thoughts from other economists I’ve asked to contribute to the blog.

Like what I wrote? Hate what I wrote? Feel free to comment below.