This week on Crash Course Economics was not so much…economics. In this economist’s view, behavioral economics is more akin to psychology or sociology, despite having the “economics” in the name. Nonetheless, we are going to talk about some of the points that Crash Course did make on economics in this weeks episode.

The Big Picture: Predicting Behavior

When economists make their models, they generally assume that people are rational and predictable. But when we look at actual human beings, it turns out that people are impulsive, shortsighted, and, a lot of times, just plain irrational.

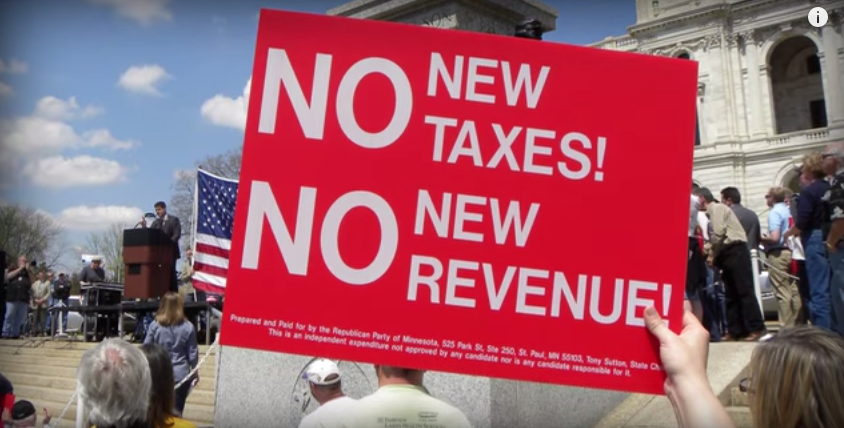

People often point to the existence of human irrational behavior to argue against economic truths that they might not like. For example, if you are arguing through economic logic that price controls make an economy worse off, a position that economists from all sides of the spectrum agree with, you might hear a response like “well, that assumes that people are acting rationally in their own self-interest, or with perfect information, but that isn’t always the case.”

While this might be true (there isn’t always perfect information, and people aren’t always rational) it doesn’t disprove any economic theories. What it does support, however, is that economics is very difficult to predict empirically. Let’s look at an example from this week’s episode:

Some grocery stores in the Washington DC tried to decrease the use of disposable plastic bags by offering five cent bonuses if customers brought reusable bags. The policy didn’t do that much. Later they tried a five-cent tax on plastic bags, and, this time, people used fewer disposable bags.

While empirical economists would be wrong in their predictions of the effects of the bag bonuses, those economists who shy away from empirical predictions (namely from the Austrian School) would only predict that there would be fewer plastic bags used than before, which is likely true.

In short, Crash Course’s big picture look at behavioral economics shows us how all those brilliant economists working for different government agencies and universities manage to get things wrong. The problem is not the theory, but the empiricism.

Lack of Information

Classical economics assumes that consumers have perfect information when making choices. That is, they know or at least can quickly access information about prices and quality, but, in reality, they often don’t. Sure, the consumer could ask around or call their friends to see if they’ve tried that type of ice cream but they’re probably not gonna do that. In this situation, consumers may act on the limited information they have, a suspiciously low price, which means either the ice cream is a great deal or it tastes like mayonnaise.

The way markets work is that the supply, demand, and price work out over time. Consumers might be cautious to any product at first, but as more people try the product and share the information about it (whether it’s on cnet, yelp, or amazon), the market tends to work itself out, even when it’s a little rocky at first. As Crash Course points out correctly, perfect information doesn’t happen all at once, but the market does move toward perfection as time goes on. As for the ice cream example, if the ice cream had a suspiciously low price but tasted like high quality ice cream, over time demand would meet the market’s expectations, although it might not happen at first. Ever heard of two buck chuck?

Nudging

Crash Course talked about a fantastic and recent theory in behavioral economics called Nudge Theory. Best explained in the book Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness, Nudge Theory recommends an opt-out system of public policymaking, where the preferred choice is made easier or more visible to to the consumer, while still allowing the consumer to choose the less desired choice:

[Behavioral Economists] wanted to see if they could get children to eat healthier by rearranging school cafeterias. They put healthier food like fruits and vegetables on eye-level shelves and less healthy foods, like desserts, in less convenient places. Classical economic theory suggests that this idea wouldn’t work since rational people would pick the brownie. But it turns out, students choose the healthier foods. Nudge theory works and it’s changing how we implement public policy.

What Crash Course failed to mention, however, is that policymakers choose to impelement Nudge theory because it is particularly libertarian. If schools really wanted kids to stop eating unhealthy foods, they could just ban them entirely. Instead, Nudge Theory retain’s the consumers’ freedom to choose, while still encouraging them to make the healthy choice.

Bubbles are Caused by Animal Spirits?

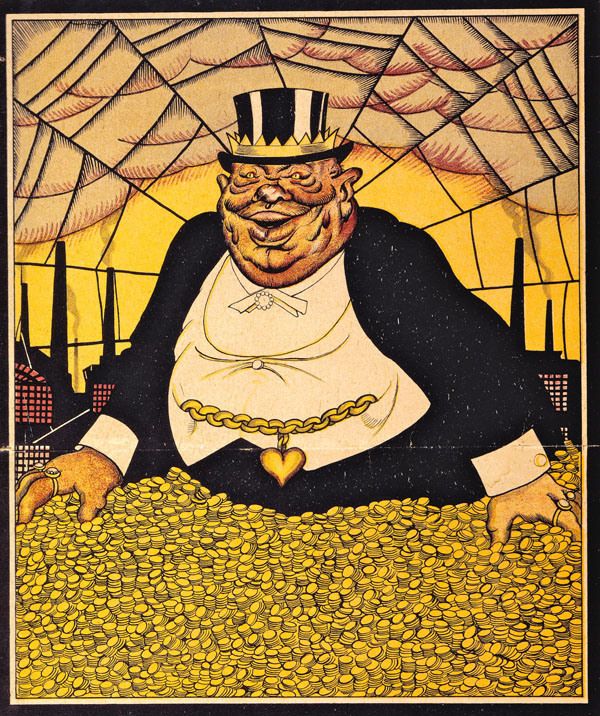

Many economists used to believe that assets, like stocks and real estate, would stay at or near their real value because cold, calculating investors would buy undervalued assets and sell overvalued assets. But that doesn’t explain bubbles: In real life, investors aren’t always cold and calculating. They can get worked up and irrational sometimes.

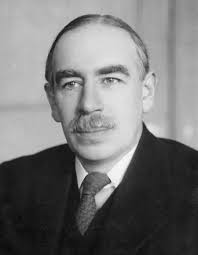

This helps explain bubbles. From the Dutch Tulip Mania of the 17th century, to the 2008 financial crisis. Investors became irrationally exuberant, and were driven not by logic, but by what economist John Maynard Keynes once called, “Animal Spirits.”

This is very strange, since back in episode 7 on bubbles and episode 12 on the 2008 financial crisis, Crash Course explained bubbles quite differently. Back then, bubbles were created by complex financial products and lack of regulation, but maybe those were only the environments to create the bubble, and it was actually the animal spirits that created the bubble all along.

If you, as an economist, are going to stop your analysis of bubbles at “animal spirits,” you might be doing your audience an injustice. People blame a lot of different things for creating the 2008 bubble (legal incentives to encourage bad lending, poor credit-rating by agencies, monetary policy), but you can’t just dust off your hands and say “it just happens” Bubbles of 2008’s magnitude don’t happen with animal spirits alone. The spirits might do the popping, but bubbles are created by other factors.

Thanks for reading, and you can look forward to a new episode reviewed every Thursday! And don’t forget to join our newsletter and our facebook group, and comment below!