If last week’s episode was meek, this week’s was a giant. There is a lot to unpack when talking about Education in general, and this episode goes from preschool to graduate school, all in one 10-minute lesson.

Unfortunately, this episode contained a lot of conclusions that were not backed up by full arguments (then again, you can only do so much in 10 minutes), and we’ll talk about some of these conclusions. There’s a lot to say about this episode, and we’ll be nailing the important points in this blog post. Let’s get started:

Education vs. Public Schooling

Crash Course begins this episode with a comment about how every country needs public schooling:

Why do governments spend billions funding universal public education? Why not just let profit seeking businesses handle it? Many argue that if education was entirely privatized it’s likely that some children would be excluded, and that would make society, as a whole, worse off.

We mentioned this in Episode 21, but there is no way anyone could make this conclusion on anything but speculation. The existence of a “free” primary and secondary school option pushes private competition out of the market, so when predicting a vastly different schooling market, economists don’t have much data to work with besides their own imagination.

Let’s also look at the numbers (given by Crash Course themselves): Public schooling costs about $12,500 per student per year. In comparison, the average private elementary school costs $7,770 per student, and private high schools cost an average of $13,030.

So public school costs about as much (or more) to provide than private school, yet generally speaking, provides worse education for the students. This is why many economists promote the idea of school vouchers, where parents can spend the tax revenue that would have gone toward public schools on the private school of their choice.

Equivocation of “Education”

Immediately after talking about the need for public schooling and its positive externalities, Crash Course talks about the benefits of education in general, including mentioning that it…

also benefits society as these individuals create art, invent cool stuff, cure diseases, and make interesting conversation at parties. More education increases productivity, GDP, and standards of living.

All of this is true, although this isn’t really an argument for state-funded education, but more for education in general. Is the public school system better at educating students in art, invention, or medicine?

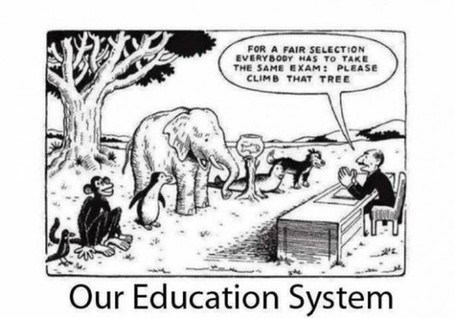

Inequality

The US has some serious problems with its education system. One of the biggest is inequality. Students from low income families tend to have lower math and reading test scores than those from higher income families. African American, Latino, and Native American students are much more likely to drop out of high school than their White or Asian counterparts.

When talking about the problems with the education system, I was surprised to see such a major focus on inequality in this Crash Course episode, especially since they already dedicated a full episode to it. I thought that Crash Course would focus on the problems with the education system (falling test scores, lack of preparation for the real world, rising tuition) and not on the racial/economic divide.

For some economists, the best way to level the playing field is to focus on funding. They argue that the government should pay for early education programs, and provide extra money for disadvantaged and low-income students.

First, economists and sociologists are very torn on whether there’s any correlation between pre-schooling and later academic achievement, and I’m surprised that Crash Course wouldn’t mention that this is highly debated.

Second, how would sending all kids to preschool solve the inequality problem? Doesn’t the US already send all kids to school from grades K – 12, and the inequality problem still exists? Can anyone please explain how government-funded preschool solves this problem?

It’s clear that the first step to improving equality is to invest in primary and secondary education.

Crash Course has isolated the educational performance data in a box. They are surprised by how students of different races/income levels succeed at different levels, and the only solution they see is for the government to put money somewhere, anywhere in the school system.

Could it be that there are other things besides education funding that could contribute to why kids of different races/incomes are performing differently? Could it be, for example, all other life circumstances, or that parents with greater income will send their kids to private schools? It’s incredible that Crash Course doesn’t consider these other factors to be an influence on educational achievement. Keep this mind for later in the video.

As a side note, the only problem with the US education system that Crash Course mentions is one of inequality. It’s not really an economist’s place to talk about the problems of the US school system, but I think most people can think of some problems other than inequality.

College and Higher Education

Crash Course starts off their discussion about college by mentioning that those who attend college are generally self-selected privileged people:

First, it takes a modicum of intelligence and dedication to even get into college. Second, you have to receive a fairly good primary and secondary education to be able to keep up with college work. Third, the students who attend college are more likely to come from well-off families with educated parents who have the time and energy to help encourage their success.

I’m not going to guess that ages of the co-hosts of the show, but as anyone who has attended college in the past 10 years can tell you, there are not filled with only smart people, and even if you don’t come from a well-off family (as many are not), you can still go to college with government loans.

But here is the real kicker:

The fact that college graduates make more money isn’t just about college. It’s also about life circumstances.

Why couldn’t Crash Course use this exact explanation when talking about difference in academic achievement between races/incomes? In other words, life circumstances are the best predictor of academic/financial success, not college degrees or preschool education funding.

Human Capital vs. Signaling

Does college actually increase your productive capacity, or does it just give you a nice thing to put on your resume for others to see? Crash Course tries to explain it here:

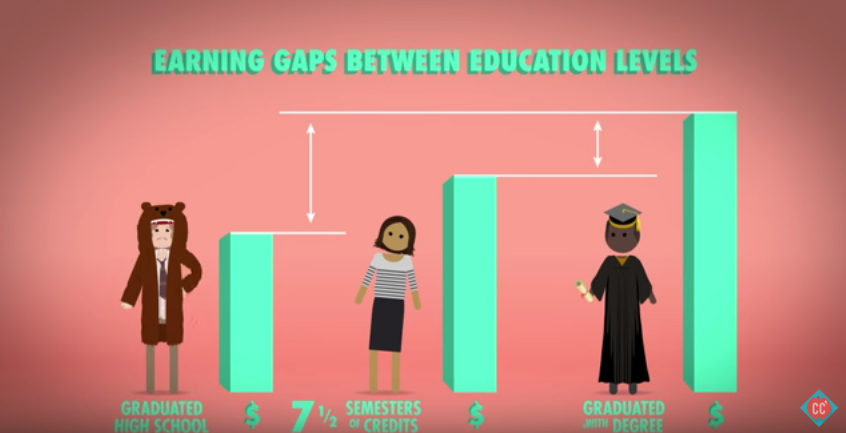

They have compared the earnings of people who have earned 7 ½ semesters worth of college credits but didn’t graduate, to people who finished and got a degree. Both groups received about the same amount of education, so if the Human Capital theory is correct, they should earn about the same amount of money. If the Signaling theory is correct, those with degrees should earn noticeably more, and they do.

It’s no surprise to most people in their 20’s and 30’s that employers are looking for that college degree, unless you work in an area that’s really all about human capital (like computer science). For most people looking to get the standard post-grad job, the employer will look at your degree and your GPA, and that’s pretty much all you can do, unless you’ve held a big job before. If you try to apply for the job without a degree, your chances are much worse, even if you are better skilled to work the job. Since a lot more people go to college these days, having the degree is no longer a bonus, but rather it’s a huge negative if you don’t have it.

But it’s a smaller gap [in income] than you would find from just comparing high school and college grads. It seems that both theories apply.

But according to Crash Course’s earlier analysis, since privileged people (with better education/skills) are more likely to self-select into college, wouldn’t that account for the difference in income between the two groups (high school graduates and those with some college education)? In other words, since Crash Course argued the barrier between high school and college mostly divides the “at least some education/skill” and “not enough education/skills” groups, wouldn’t this self-selection explain the differences in income?

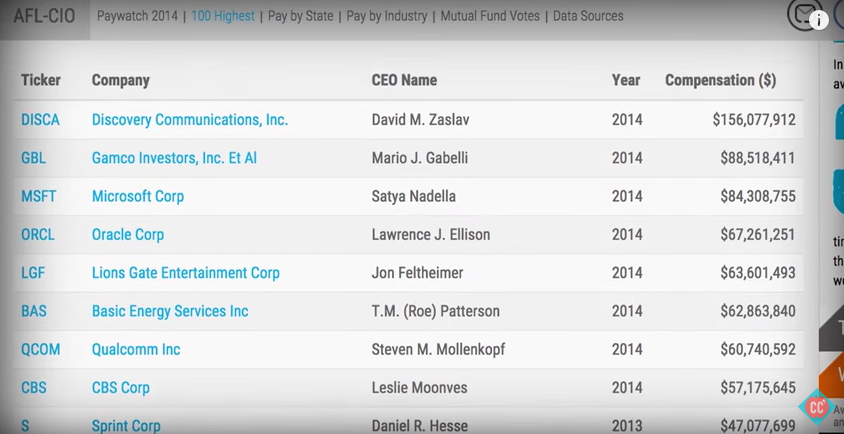

High Tuition

The rising costs of college education and the enormous amount of student debt are subjects barely covered in this episode, and yet, it has so much to do with economics.

In short, since the federal government allows students to borrow money to pay for college, regardless of the price, colleges have no incentive to keep costs low like other businesses do. They can feel free to increase tuition year after year, and the demand curve remains inelastic. In basic terms, government loans skyrocket the demand for education, and with the supply of universities staying about the same, the price has to rise. It was very surprising that Crash Course made no mention of this, even though it would have been perfect for this week’s episode.

Does your brain hurt after this episode? You’re not alone. This one was a struggle. Thanks for reading and be sure to come back every Thursday for a fresh post. And don’t forget to join our newsletter and our facebook group, and comment below!