Debt and Interest Rates

Toward the end of the video, our co-host Adriene talks about default, a terrible thing for any country. After all this gloomy talk about how much debt the United States has, Adriene brings up a positive point:

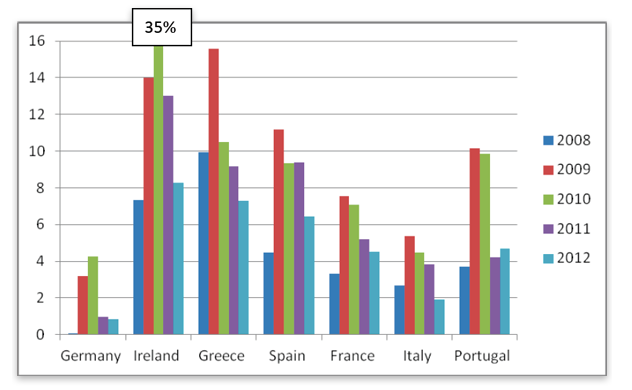

There is good news for the US. First, both American and foreign lenders charge the US government extremely low interest on its loans. That means they are confident in the government’s ability to pay them back. And the low interest rates actually make it easier for the government to pay.

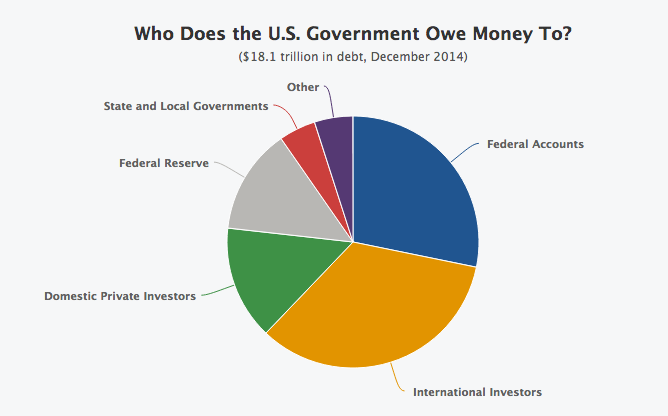

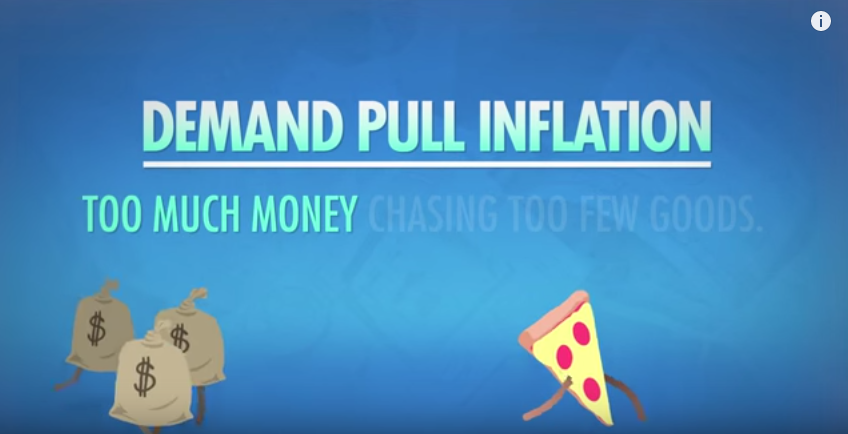

This is true, but Adriene fails fails to mention why the interest rates are so low in the first place. Lenders don’t just give the government a good deal because they are feeling generous. US interest rates are controlled by the Federal Reserve, and people (along with companies and foreign governments) lend the government money at the rate controlled by the US government.

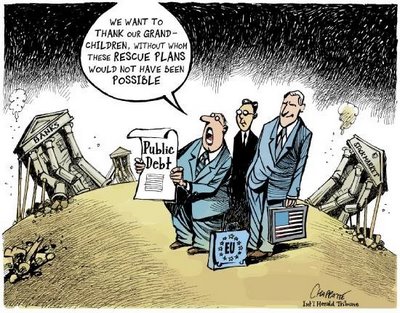

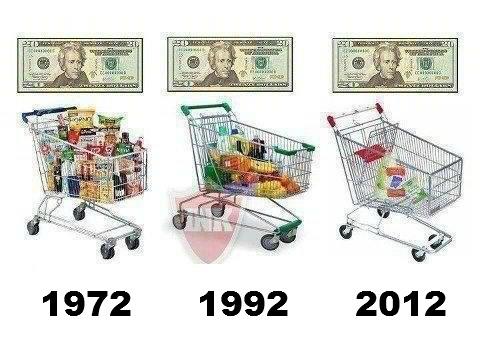

The US government also controls money printing and taxing hundreds of millions of people, so you can be pretty sure that you are going to be paid back one way or another But what if you’re paid back in future US Dollars that have been completely devalued?

There is another reason why people are confident in the government’s ability to pay back the loans (that are worth something): reserve currency status. In international trade, businesses (or governments) can always set the prices of goods they are trading in US dollars, since other countries also accept US dollars. For example, if India is selling goods to Australia, India would prefer to receive US Dollars, because then India could buy goods from China, who also accepts US Dollars.

Since the US Dollar is the reserve currency, it is afforded certain privileges that other countries’ currencies do not have. With foreign businesses and governments trading and holding on to US dollars, the demand for the US dollar remains consistantly high.

Imagine if you were a business holding on to Thailand’s currency, the Baht, for some reason. If Thailand announced that it would lower its interest rates and launch its own QE program, you might be worried that the value of your Thai Baht would decrease as Thailand’s central bank is printing more more (and you would be right). The Baht’s future value, to you, is unpredictable, and you wouldn’t want to stick around to see what happens to your savings.

Imagine, however, that you were instead holding US Dollars. The US Federal Reserve starts printing money, weakening your savings, but everyone country still trades in US Dollars, and you need to hold on to your US Dollars for possible future international purchases. Switching to a new reserve currency would require a lot of international governmental collaboration, and this doesn’t seem to be happening anytime soon.

Maybe Things Aren’t So Bad

While it may seem like the growing US deficit and historic debt will bankrupt the economy, Crash Course says it’s not that simple:

So is all this deficit and debt going to destroy the American way of life? Like most things in economics and Crash Course, the answer is complicated, and it depends a lot on what you’re looking at in addition to your political point of view. Looking at debt from the past or even the present is a good way to have political arguments, but it may not be a great way to think about the future.

Right now health care spending is driving the debt higher, but if a massive pandemic kills of half the world or there’s a zombie apocalypse, aften an initial spike, those health care costs are going to fall, and frankly, in that case, the national debt and deficit spending will be the least of our worries.

Translation: I know it looks like rising health care costs and government spending are going to destroy American prosperity, but maybe not! There might be a pandemic or a zombie apocalypse! Then the debt won’t matter.

Is this the best case scenario that Crash Course can think of to assure as that the debt and deficit are not a problem, or is this a roundabout way of saying that there really is something to worry about? I don’t know what Crash Course was trying to get at with this sentence.

This is where Crash Course strays from their previously Keynesian bias. A real Keynesian would say that the debt can continue to rise, as long as other countries keep the dollar as a reserve currency and people still have faith, the dollar will be fine. If other institutions are not concerned about our currency now (considering the projected rise in the deficit and no chance that the US will start paying back its debt), then will they ever?

I can’t give you much of an optomistic predeiction, and apparently, neither can Crash Course. But what do you, esteemed Crash Course Criticism reader, think will happen with the future of the US dollar?

Like what I wrote? Hate it? Drop some feedback in the comments. Also sign up for the Newsletter.